Update June 21: Providence nurses at six hospitals across Oregon say they were barred from returning to work Friday in what's called a "lockout" after taking part in a three-day strike over stalled labor negotiations.

Nurses are now picketing in front of Providence facilities Friday and Saturday.

According to the Oregon Nurses Association (ONA), the union representing nurses from Providence, the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) "has confirmed violations of Oregon's nurse staffing law by Providence."

That law establishes minimum staffing ratios to ensure quality patient care and prevent nurses from burning out due to untenable patient loads.

The ONA claims Providence didn't follow the correct procedure for implementing staffing plans.

"Providence submitted staffing plans to OHA for approval that were never agreed upon by nurses and were unilaterally adopted by management without the required approval from the nurse staffing committee," ONA stated Friday in a news release. "According to OHA, this action violates Oregon's staffing law, as ONA-represented nurses have been claiming."

Lockouts are typically initiated by an employer as a tactic to try to force union-represented employees to agree to a labor contract.

Original story below

Published: June 20, 2:06pm

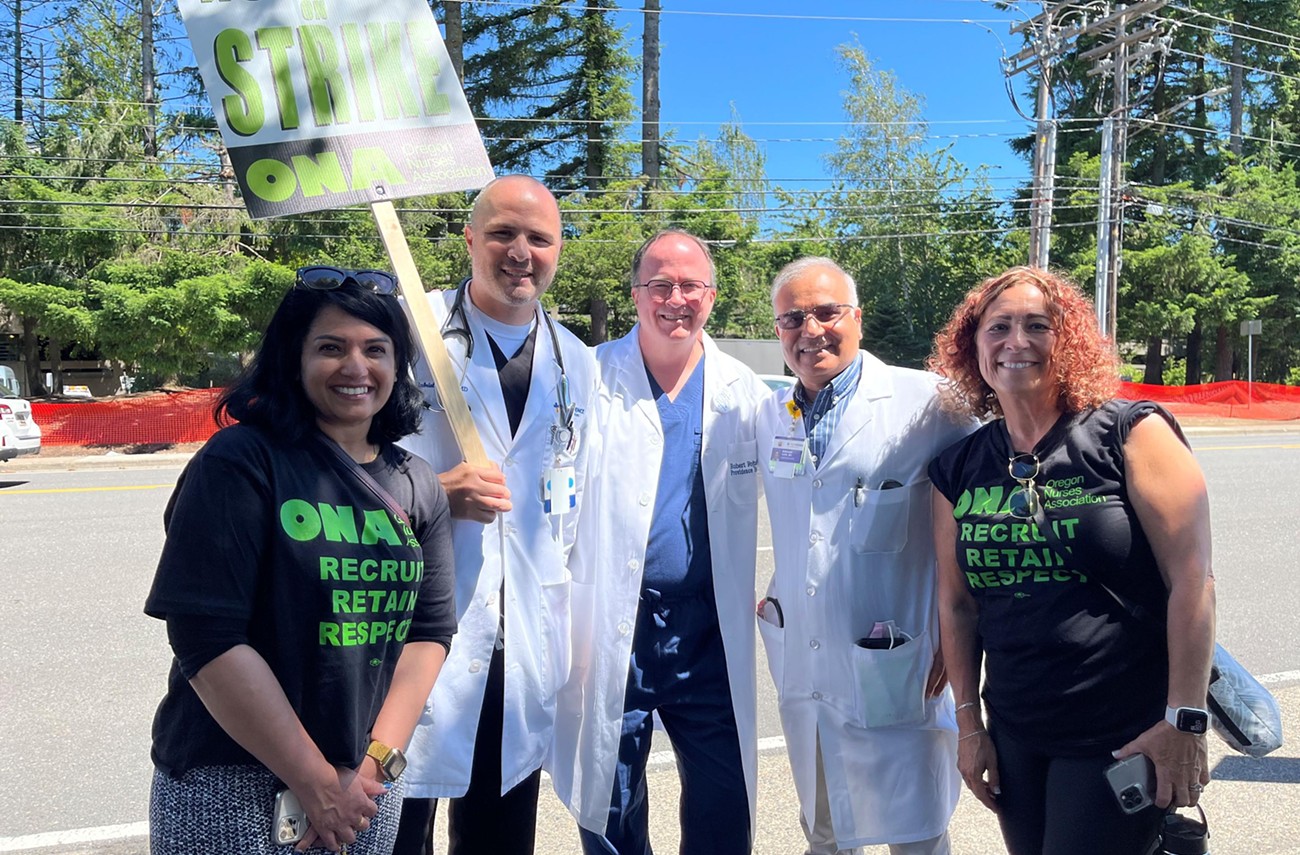

The strike, which saw some 3,000 nurses walk out of work on Tuesday, is the largest health care worker strike in the state in decades. Among the six hospitals affected is Providence St. Vincent Medical Center on Portland's west edge, the largest hospital in the state.

Katie Moslander, a staff nurse in the orthopedic unit at St. Vincent, says the strike thus far has been a positive experience.

“It was a hard thing to make the decision to come out to do it—it was a hard shift on Sunday, just knowing I'm not going to see these patients again this week—but it has been an overwhelmingly great feeling of camaraderie with my fellow nurses,” she says.

This is not the first strike at Providence hospitals in recent years. Last June, almost a year ago exactly, nearly 2,000 Providence nurses in Portland and Seaside launched a strike for better wages and benefits.

The array of issues in the current contract negotiations between Providence and nurses represented by the Oregon Nurses Association (ONA) are similar: nurses are seeking improved wages, lower health care costs, and safe staffing levels.

One difference, though, is the fallout from Oregon’s recently-passed safe staffing law. The law, which the ONA described as a “game changer,” made Oregon the second state in the country to adopt mandatory nurse staffing ratios and ended the so-called “buddy break” system that required nurses to cover their colleagues’ patient loads when they took breaks.

Moslander praised the law, which went into effect on June 1, but said the rollout has had unintended consequences.

water, and ice to help strikers beat the heat. oregon nurses association

The law ensures hospitals cannot assign more than a certain number of patients to each nurse, but Kathy Keane, a staff nurse at St. Vincent and the chairperson of the nurses’ bargaining committee, says Providence has taken to assigning each nurse the maximum allowable number of patients—without taking into consideration the level of care each patient needs.

“Their interpretation of law is to put everybody at the maximum ratio, regardless of how ill a patient is,” Keane says.

The result, nurses say, is that they frequently lack the time to get to know patients and provide adequate care. Providence, for its part, has argued that if nurses have issues with the current staffing setup, ONA and allied unions are to blame.

“The union declared a major victory when the law passed—and again, it was passed with a coalition of unions and health systems,” Providence wrote in a statement released Wednesday. “If union leaders want to change the law they championed, they should go back to the legislature, instead of striking over something Providence can’t change.”

Staffing is far from the only issue the nurses and hospitals remain at odds over. Nurses, who are bargaining for separate contracts at each individual hospital, also want pay raises that they say would bring Providence in line with other area hospitals.

Providence says it has offered raises of approximately 10 percent in the first year of new contracts across the six striking hospitals, but nurses have said the raises offered for the following years of the contract are just 3 percent—not enough to keep up with the current rate of inflation.

In any case, Moslander says, people are voting with their feet.

“You can say whatever amount is a competitive wage to you as an organization, but if people are leaving, I think that's a problem,” she says.

Health care costs are also an issue. Providence offers its own health insurance plan and covers a high percentage of premiums compared to other plans, but Keane says high deductibles and copays have made the coverage unaffordable.

“I know that I’ve spoken with a couple of nurses just within the last several weeks that have had certain tests recommended by their doctors for diagnostic reasons because they’re having symptoms of various things, and two of them have said they've opted to not pursue them because the cost is just too high,” Keane says.

Keane herself is on her husband’s health insurance plan to save money, even though his plan doesn’t provide nearly the same standard of coverage the Providence plan does.

Nurses argue that raising pay, bringing health care costs down, and improving staffing levels, would help Providence hospitals retain staff—which, nurses say, is a major issue. Turnover rates in nursing generally have skyrocketed in the aftermath of the pandemic, with a number of nurses leaving the profession while others have changed hospitals.

Moslander says she thinks nurses would generally rather stay in their jobs than bounce around to different hospitals, but have to be realistic about the financial incentives.

“People want to stay with their colleagues,” she says. “People want to stay where they’ve built a career. But those economic things, sometimes you just don't have a choice. I’ve got three kids, a lot of people are single parents—you’ve got to do what you’ve got to do.”

The nurses are expected to end their coordinated strikes and return to work on Friday. In the meantime, Providence has worked with a national firm to hire replacement workers to operate their hospitals. A select number of procedures have been postponed.

Keane says she hopes to return to the bargaining table following the strike’s conclusion, although there isn’t currently another bargaining session between the two sides scheduled. The two sides have been in federal mediation this spring leading up to the strike date.

The current strike at Providence, like the strike last year as well as a contentious contract negotiation at Kaiser, is taking place in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic—an event that had seismic consequences on nursing and in the health care industry more broadly.

One of the consequences, Keane says, is that it helped remind nurses of their worth.

“I guess we’ve always just taken for granted that we just do what we do and it’s not a big deal, but I think we finally realized that what we do is a really big deal,” Keane says. “And we’re valuable.”

Courtney Vaughn contributed reporting to this story.